Share Magazine Winter 2015

Changing Cultures of Practice. Bringing the ATLASS approach to Scottish Autism's services

20/10/2015

David Harkins

Since 2013 practitioners from Scottish Autism have been training in the ATLASS (Autism Training with Low Arousal Support Services) approach to supporting people with autism. As the organisation looks to embed the approach into everyday practice, David Harkins and Vicky McMillan of Scottish Autism, provide a background for those that are unfamiliar with ATLASS. We also reflect on experiences of the approach in practice and our plans for incorporating ATLASS into our work across the organisation.

What is ATLASS?

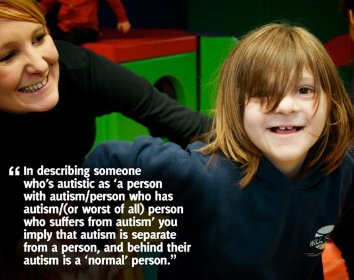

The ATLASS model was developed by psychologists from the Studio 3 organisation including Michael McCreadie, who is also a Practice Associate of Scottish Autism’s Centre for Practice Innovation. ATLASS entails a holistic approach to autism support that focuses on the wellbeing and happiness of the individuals in our services. The programme recognises the impact of stress on wellbeing, so rather than focusing on ‘challenging behaviour’ as something to be treated on its own, ATLASS-trained practitioners focus on stress reduction in service environments, positive interactions between staff and those they support, and the importance of health and exercise for wellbeing. The approach is holistic, recognises that stress is transactional and that reducing stress among parents and practitioners helps provide a positive environment for the individuals that we support: positive interactions and relationships benefit everyone. This helps us move on from focusing solely on the individual and adapting ‘their behaviour’ to reflect on our practice in a way that empowers us all. The ATLASS model examines the spiritual, mental, environment, social, physical, and emotional wellbeing of individuals both individually and collectively.

The ATLASS training gives practitioners some key learning points in developing low stress support. These included an understanding of the physiology of stress, why it occurs, and how exercise and positive experiences can counter the effects. Participants are guided through a better understanding of autism, sensory perception, analysing the stress transaction, coping strategies for stress as well as insights into their own practice that include change talk and motivation, the use of mindfulness and reflection in autism practice, and on happiness and wellbeing as focuses of practice. The training includes numerous practical insights into identifying causes of stress in environments and interactions, and practitioners are mentored through the process of developing stress reduction programmes for individuals.

ATLASS in practice

One of the stress reduction programmes undertaken by the initial ATLASS cohort was provided by the staff team for ‘Emma’. Emma is an autistic woman in her mid-40s who lives in one of Scottish Autism’s supported living services, as well as attending our day resources. Emma has often displayed high levels of anxiety manifested in self-harm and verbal and physical attacks on staff.

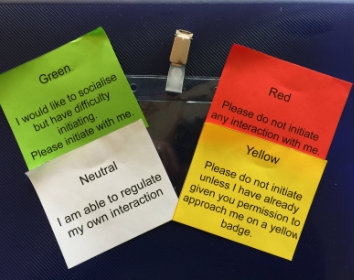

In collaboration with Emma and her team, the ATLASS-trained practitioner identified where the particular stressors in Emma’s life lay. Key factors included having her routines, or her thought processes disturbed; transition from one activity to another (particularly if activities do not have clear beginnings or endings); and changes to the environment (particularly increases in noise). The team also noticed that staff were communicating with Emma in different ways to one another and were not always alert to environmental stressors that may impede Emma’s processing.

The stress reduction plan has therefore involved supporting Emma to recognise her own signs of stress (through visual aids and references), validating the principle she can leave noisy or stressful environments if she needs to, and teaching relaxation skills such as breathing. Support staff have also worked on their mindfulness to be alert to environmental stressors and to be conscious of the way that they communicate with Emma. This includes important changes like giving Emma full attention (rather than multi-tasking while supporting Emma) ensuring that they always say Emma’s name when addressing her, ensuring that the environment is calm and quiet, and providing clear markers to begin and end activities. Emma also enjoys using pet names that she has created for herself. Although this may have been unusual to some people, staff were encouraged to use these terms of address, which Emma finds meaningful and fun.

The ATLASS practitioner also worked with Emma to identify things that she liked doing. Although practitioners were sensitive to the possibility of sensory overload, Emma emphasised that she enjoys pampering and aromatherapy which she is given regular opportunities to do. The team also looked at increasing other activities that aid Emma’s wellbeing and health such as extending her swimming sessions. Emma enjoys dancing at home and in her day service, and so Emma has also joined a Zumba class that she enjoys.

Many of these kinds of practice changes will be intuitive to some autism practitioners, or resonate with their existing practice ethos. Others, however, may still look at ‘challenging behaviour’ in isolation, and think about reacting to those situations as they arise rather than understanding holistically what may cause stress or aid wellbeing. The ATLASS stress reduction plan gives an opportunity for staff and the people they support to identify stressors and wellbeing activities collectively and, through encouraging mindful practice and interactions, encourages practitioners to be conscious of their own communication and the service environment.

Changing practice collectively

Two cohorts of practitioners (a total of 20 staff) have now been through the ATLASS training, the first in 2013-14, the second in 2015. The training comprises nine days in all with participants undertaking case studies between sessions and keeping a reflective learning log throughout the process. The first cohort has gone on to undertake a masterclass at Studio 3’s base in

Warwickshire, which allows them to train others in ATLASS. Masterclass participants have formed a working group to plan how to roll out the approach across Scottish Autism. Members of the working group have delivered workshops at our annual staff conference and to all the practice staff at New Struan School. The approach has been incorporated into many elements of Scottish Autism’s learning and development programmes including mandatory training. ATLASS themes are also influencing the redesign of the organisation’s support plans and will be threaded throughout the new documents.

We have been helped by our partnership with the Heimdal organisation in Denmark who are also moving to an ATLASS model of support. Our Danish colleagues have shared valuable insights into their own experience of ATLASS and we have undertaken reciprocal visits to compare our approaches and learn from each other through a process of peer sharing and support.

All trained practitioners agree that ATLASS represents a significant shift in thinking. Making the approach work will require changes to our cultures of practice, but the benefits for all of us will be significant if we inculcate a focus on happiness and wellbeing across Scottish Autism’s services.