Autism Understanding Among Police Officers in Scotland

Dr Carrie Ballantyne, Lecturer

It is not uncommon for an autistic person to come into contact with the criminal justice system, either as a victim of crime or a suspect. However, a recently accumulated body of research shows that autistic people’s experiences within the Criminal Justice System are largely negative. It is therefore vital that the Police have relevant training, knowledge and awareness of autism to allow for inclusive practices and an appropriate framework for working with neurodivergent people. Our recent study based at the University of the West of Scotland aimed to look at how police officers felt about their autism knowledge and interactions with autistic people and where they felt better understanding would help.

Characteristics of autism make people particularly vulnerable to misunderstandings during different stages of police interactions. For example:

1) During ‘First response’ situations, stress and anxiety may exacerbate difficulties with perspective taking, or provoke undesired responses (such as aggressive behaviour) leading to further anxiety. Damian Milton’s ‘double empathy problem’ also suggests that non-autistic police officers may have difficulty understanding the perspective of autistic people, making it difficult to interpret their intentions. Sensory difficulties to bright lights and loud sounds may cause further stress in a first response situation, if the responding officer is not appropriately trained.

2) If an autistic person is taken into custody, changes in routine and environment are likely to be traumatic and stressful, particularly for those with sensory issues. Research by Laura Crane and colleagues at University College London found that autistic suspects are often not accommodated in custody suitably. Difficulties understanding the way that information is communicated may mean that people misunderstand their rights and cautions. Restraining suspects, to reduce harm to self or others, can also lead to adverse reactions, with police often having inadequate training, environments or tools to effectively engage with autistic detainees.

3) Interview processes are particularly difficult for autistic people. Difficulties in recalling the temporal order of experiences or context can be particularly problematic and may even lead to somebody unintentionally incriminating themselves. Difficulties with social interaction can also be a challenge: research reports autistic people giving responses that they believe to be socially desirable or agreeing with inaccurate statements given by a police officer in order to please them without realising the consequences.

Recognition of autism and autistic traits may be difficult for police officers when initially attending the scene of a crime. This means that there has to be opportunity for disclosure of diagnosis and for the officer to then act appropriately, with awareness of difficulties that people may experience. Autistic people often feel negatively stereotyped by disclosing their diagnosis, which may be due to lack of understanding. Frontline officers receive little training on autism. Previous research has shown that police officers can misunderstand the differences between developmental disabilities and mental health difficulties, for example.

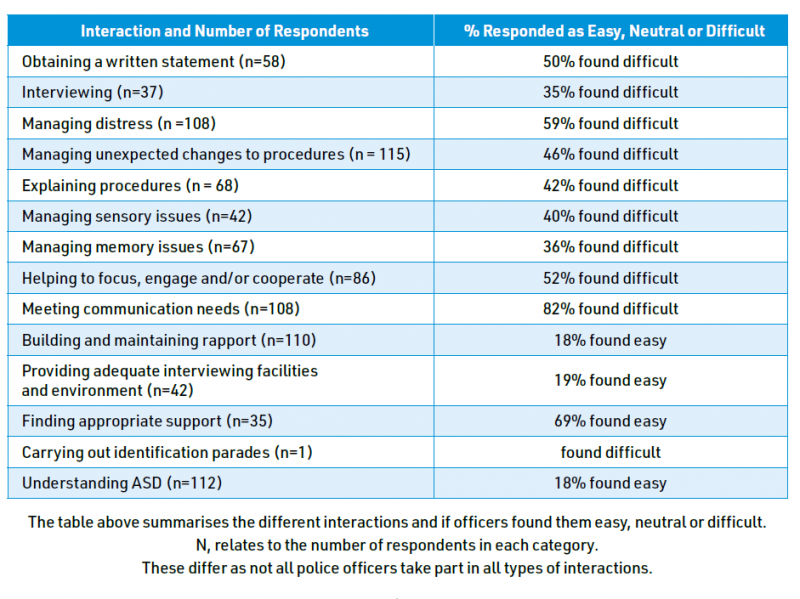

Our own study used an online survey to investigate the experience and views of 119 police officers from Police Scotland around working with autistic people. These were comprised of 15 Custody Officers, 8 Police Inspectors, 8 Superintendents, 24 Community Support Officers, 10 Police Sergeants and 54 Police Constables. This questionnaire asked officers what they found easy or difficult in their interactions with autistic people.

Overall, only 35% of officers asked were satisfied with how they had worked with autistic individuals, pointing to a need for better understanding of autism and autistic people’s needs.

Officers were also asked what the barriers were that they faced in their role in interactions with autistic people and what they felt was good practice. Officers not only cited a lack of training but also the type of training they received as a barrier to better practice. Some felt that online training dealt in abstract information and that more bespoke, specialist training is often only given to those who are high ranking. Other barriers related to time constraints and also catering to autism-specific needs, particularly in custody suites and interview practice.

However, all is not lost as there does appear to be awareness of autism and the variability of autistic traits and behaviours with the Scottish Police Force. When asked about what police officers felt was good practice, autism awareness was a theme, with officers reporting that they understood that particular behaviours and misunderstandings may be a reflection of a person’s communication style rather than the individual being difficult or uncooperative. Another theme that emerged when discussing good practice was that police officers knew how to access autism-specific support.

The study showed that although there is still much progress to be made, especially within training, there is a movement and a recognition by police officers that more inclusive approaches to working with autistic people are needed. A move away from online training packs, to more immersive autism training could be one way to improve. The research also suggested that Police Scotland is somewhat fragmented in the way that it operates, and so sharing good practice amongst different divisions will be imperative to improving the way officers engage with autistic people.