Grasping the Nettle by the Horns

Jeanie Macfarlane, Senior Autism Advisor, Scottish Autism

Living and Working with my Autistic Thinking

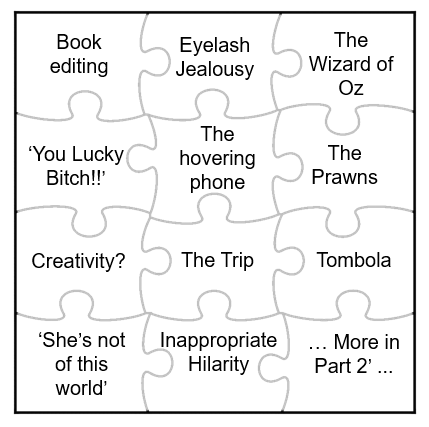

During a recent presentation, I discussed ‘reclaiming the jigsaw’ from negative associations within the autism world; a desire I had held since surfacing from sleep on the night of my autism diagnosis with the satisfying sensation of pressing the final piece of a jigsaw neatly into place. That night my personal jigsaw was in many ways complete, but two years on, fearing negative connotations, this analogy remained unused. I’m now reclaiming it to describe the many puzzle pieces that lingered in my brain for decades until the bigger picture of an autism diagnosis finally enabled their correct assembly.

Many of my puzzle pieces relate to things people have said and done that bewildered or confused me. I have real difficulty getting the bigger picture; summarising; drawing conclusions and have a talent for ‘getting the wrong end of the stick’. It’s taken me decades to feel at home with metaphors like the one I just used and I’ll often come out with a hybrid of two. Hence my title. Yes, I have actually said that! My diagnosis has gradually lessened the discomfort, embarrassment and sheer bewilderment of such situations (or I wouldn’t be sharing them!). It’s also helped me realise that while they still occur, instead of agonisingly ruminating I can laugh and share them as insights into neurodivergent thinking.

So here are several jigsaw pieces, intended to humorously inform and support colleagues and managers of those who think and interact that bit differently. While these situations are not dissimilar to those experienced by many neurotypicals, it is the quantity, frequency and underlying reasons that finally led to my diagnosis.

‘Eyelash jealousy’

Laura, my adorable sister, was blessed with thick, curly blond hair; huge blue eyes and long lustrous eyelashes. Naturally, I experienced extreme jealousy when ousted as only child and it didn’t help that she was gorgeous. I have no recollection of this anecdote, but apparently when I was four or five I took the scissors to her lustrous lashes. No injury done, but while I was always considered a kind, compassionate child with a love for animals, a number of situations stand out where probable difficulties around theory of mind affected my natural compassion.

‘The Wizard of Oz’

Probably my first, very uncomfortable, realisation that I fitted more closely with the autistic spectrum than I’d thought came about 20 years ago when studying for an Autism degree. I was finally getting to grips with a concept I’d been struggling to grasp fully: the development of a ‘theory of mind’ (ToM). I literally came out in a cold sweat as I experienced a flashback to childhood where I acquired a new insight into another person’s thinking. At first I thought I had been maybe nine years old but then my cold sweat became even colder and sweatier as I realised that, no, I was in high school so at least age 11:

Most evenings my middle-aged neighbour would call on me to cycle with her to her housekeeping job. Sometimes she behaved a bit erratically. On this occasion, she spontaneously burst into song: ‘We’re off to see the wizard….the wonderful wizard of Oz…’. I was acutely embarrassed, although no-one else was around. So, I let her get ahead of me, then zoomed down a path and hid for what felt like ages. I heard her calling my name repeatedly, getting distant then closer, but never actually finding me. It was then that I distinctly realised that she was worried about me, but more than that, that she wasn’t just an embarrassing entity singing loudly and oddly but that she had her own set of feelings.

It was pretty scary realising that while I had always believed myself to be kind, generous and compassionate, this memory indicated difficulties very much akin to what I was discovering about Theory of Mind and autism. Although I obviously had enough understanding of others’ minds to be able to hide (and had enjoyed playing hide and seek when younger, too), this realisation of my delayed empathic understanding only served to reinforce my feeling of being a late-maturing social outsider.

‘The Trip’

I was 11 years old when, walking into the geography classroom, I stumbled over the doorstep. I was a clumsy child and my family nicknamed me ‘elephant’. My teacher saw me stumble and said, with a very straight face, ‘did you have a good trip?’

I had returned from a family holiday several weeks previously and, with my detail focus, this was the only logical reason for me to think he’d asked this. I was in my adulthood before I realised his meaning!

‘The Hovering Phone’

A recent example involved my colleague adjusting her phone on a level plane at arm’s length and parallel to her shoulder. How curious! All I could think of was the similarity between her actions and those of my husband, several weeks earlier, testing a compass app. Nevertheless, we were packing up after an intense training delivery, so why was she testing a compass? Even with my fragmented thinking, the context was wrong! Eventually I just asked her, a vulnerability I would never have exposed prior to disclosing my diagnosis. The answer was simple: ‘taking photos of your flipcharts!’ She’d arranged them on a table, something my brain hadn’t even processed!

A similar example was arriving late for an important meeting. I scanned visually for the projector I’d requested in advance, eventually asking for it. ‘It’s there on the table Jeanie!’ I was informed. Indeed it was; I hadn’t seen it as my stress-induced concept was of a black projector, not the white one ready and waiting for me!

‘The Prawns’

Started on sink duties in my first hotel job, aged 15, I was told to bin everything that arrived on the draining board. So guess what happened to the two colanders of defrosting prawns?

I convinced myself my literality was acceptable due to my vegetarianism but was aware of the self-restraint expressed by the manager: she turned away, tight lipped. Today however my jigsaw builds to reveal more: I link this episode to her subsequent surprise at my decent O-grade results. In retrospect I’m convinced she was trying to make sense of my skewed developmental profile after experiencing my social naiveties and errors.

‘Tombola’

In my early 30s, helping at my ex-mother-in-law’s fundraising fete, she put me in charge of Tombola, hastily instructing me before rushing off. However, I had never done Tombola and couldn’t process her rapid instructions or see the bigger picture of what to do.

Later she said she’d seen a look of pure terror on my face but been compelled to move on as she had so much to do and also (intuitively; she was good with, and to, me) knew I’d figure it out best if left alone. Sure enough, I processed the visual cues on the stall for meaning then knew what to do. It must have worked out - I can’t remember any more!

Only recently have I learned that if I don’t understand something I shouldn’t panic but spend a bit longer processing (and, sadly, ‘masking’) and it should start to make sense. In ‘rapid response’ situations, this isn’t helpful but it may be the only way we can respond. How would you recognise and support a colleague struggling in this way?

Inappropriate hilarity

Perhaps this is natural enough in childhood. Laughing uproariously at my granddad falling when I was 6, or deliberately tri-cycling hard into my ‘friend’ at the same age when she came out of the house with a sheet draped over her (as a ghost) could possibly be understood in this context. But then we get to the teenage years and my hilarity at pulling the chair away just as a friend was lowering herself onto it. She damaged her coccyx. Unfortunately, it didn’t stop there and in my mid-twenties, I found it hilarious when a colleague slipped on a wet floor – unfortunately, she injured herself too. I think these incidents were totally out of character for me but perhaps the developmental aspect of what is going on here will help you to understand when similar situations arise with other autistic people. We aren’t being cruel or heartless but developmentally we may be taking in the surface details first and responding to these before, perhaps, going on to process the gravity of the situation and responding more appropriately.

‘You Lucky Bitch!’

Now 19, travelling home with a colleague twice my age, I responded to her small talk feeling, as usual, uncomfortable, ‘different’ and out of my depth. My social mimicry kicked in when she described her upcoming holiday. What did I reply? I repeated, perfectly matched for pitch and tone, what school-friends had often said: ‘you lucky bitch!’ Instantly I realised my error (my emotional perception always seems on hyper-alert) as I saw a rapidly disguised look of surprise or shock on her face and knew I’d got it wrong, yet again.

Jeanie (aged 5) engaging in some flow activity

The Book Editor

In my teens, I’d spend part of my evenings very neatly re-doing my class notes in beautiful handwriting. This provided me with immeasurable satisfaction and pride. Errors in grammar, spelling and punctuation always leaped out at me and were often what I noticed before gathering the overall meaning. In adulthood, I realised that others often don’t even notice these, and I now feel particularly pedantic; the temptation to correct others’ work has always been huge, It’s even been suggested, sarcastically I’m sure, that I’d make a good book editor! I can very much align myself with an autistic individual whose staff team I supported who insisted on altering others’ writing and correcting times on their watches and clocks when these didn’t match his perception of how they should appear. Sadly, with Spell-Check taking care of things for me for many years, I now make just as many errors as other people but unfortunately don’t see them so easily in my own work!

Creativity?

I sometimes feel I’ve lived a lie of creativity. My parents’ image of me was one of a wonderfully original, creative, artistic child (i.e. a photo-fit of my Mum!).

Teachers, peers and adult friends appeared to share this view. But how true was it? Certainly, I was good at reproducing images; spelling and grammar and descriptive writing but is that creativity? Looking at what remains of my work, I can see that, for example, my early adolescent attempts at writing a children’s book did a nice job of plagiarising my then idol, Beatrix Potter, right down to the tone and illustrations.

I felt I let my Mum down (a recognised artist in her day) in that I struggled to appreciate and interpret poetry, abstract art and the finer aspects of literature. I felt stupid; just not ‘getting it’ and was forced to mask and act.

I entered Art School with a very fixed notion of pursuing highly detailed, figurative book illustration. This seemed to set alarm bells ringing and the rallying call of my art teachers since primary school to ‘loosen up’ was now taken up by my tutors. I felt completely ‘at sea’ (totally lost, bewildered, and out of my comfort zone; I now vividly remember and re-experience the physical impact on me) in my first, highly interpretive, Fine Art Humanities lecture.

Until, that is, I later took the Botanical Illustration course at the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh where my tutor, Paul Nesbitt, celebrated and nurtured my work. Give me a template, be this an object to draw; a garden design to inspire or a defined framework for a project, and I will usually find ways of extending it; even with creativity. However, I can be totally lost without this initial structure.

Perhaps this is why, in my work with autistic individuals as an autism advisor, I thrived on delivering assessments which had a detailed structure, and why (initially), I held such issue with managers who suggested that stand-alone sections of these assessments could be administered informally! Oh, the joy of now having an explanation for my whole life!

“She’s not of this world”

After we split up, my ex reported to me that his mother, with whom I’d had a very good relationship, had made this observation about me. Says it all, really…

Since adulthood I’ve been aware of ‘not going down quite right’ socially – there’s a fleeting look in a person’s eyes and no matter how they gloss over it my discomfort remains. Sometimes this is how I learn what not to do or say, but sharing my diagnosis has helped immensely and, with it, I can piece together my lifelong literality, social unease and detail focus, satisfyingly connecting the jigsaw pieces.

Despite my current positivity and humour, I’m building a picture of social discomfort; processing differences (often difficulties); and relentless self-scrutiny leading to difficulties at work; paranoia and declining mental health. No wonder I, like so many others (with a few unhelpful nudges from those who seem determined to make undiagnosed - and hence, to them, no doubt inexplicable - behaviours even more uncomfortable to us), descended into a spiral of heightened anxiety and clinical depression. Nevertheless, thanks to the input of wonderful people (including employers and colleagues at Scottish Autism, where wellbeing is at the heart of our ethos) my mental health has improved to the point where I feel I can share my experiences to help others. Selfishly, I find this is quite cathartic, too.

So finally in my 50’s, jigsaw complete but often still grappling with figures of speech such as mixing up those of my title, instead of ‘grasping the nettle’ and ‘grabbing the bull by the horns’ I do both at the same time, reclaiming the jigsaw as my metaphor to share my journey through autistic employment!

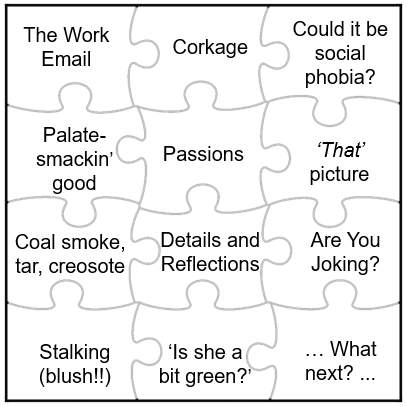

Read part 2 here