Not That Complicated

Sonny Hallett, Chair of Autistic Mutual Aid Society Edinburgh (AMASE)

Mental health struggles are common within the autistic community. Autistic people are, according to some studies, up to nine times more likely to die by suicide (i). When autistic people speak with each other about mental health, stories abound about not being understood by professionals, not getting support, and not being taken seriously. It was partly because these stories are so common that we decided to launch the AMASE (Autistic Mutual Aid Society Edinburgh) mental health survey last year, exploring autistic adults’ experiences with seeking mental health support in Scotland, followed by a report on its findings (ii) (quotes in the subheadings are from respondents). The links between being autistic and struggling with things like depression and anxiety are well known, but we know through common stories in the community that the problem isn’t simply that autistic people are too often not ok, but that we are not being adequately supported or believed when we are not ok.

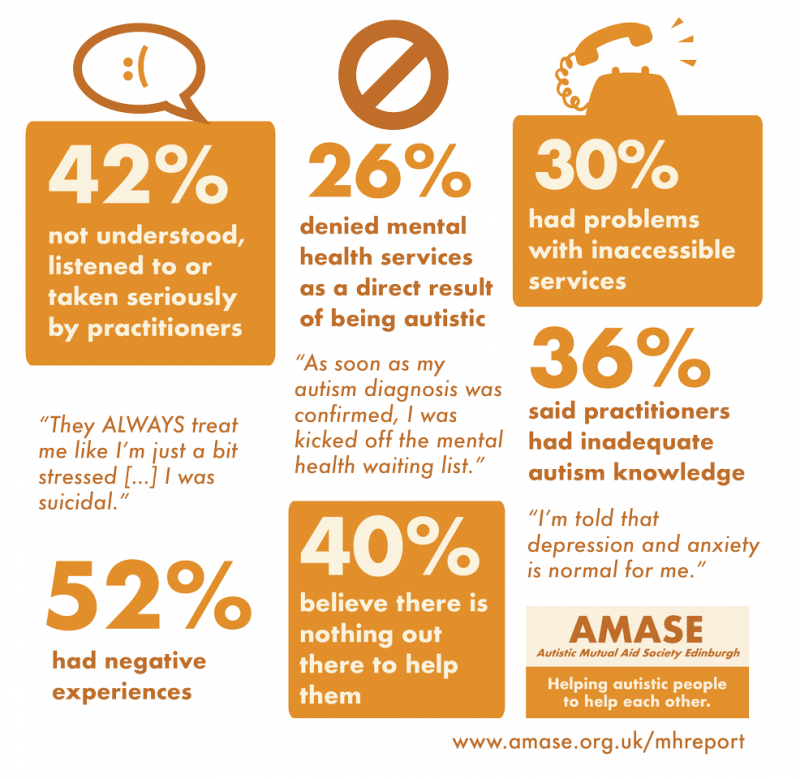

The first of autistic academic Damian Milton’s Ten Rules for Developing Challenging Behaviour (iii) is, “if you don’t understand me, call me complex”. It is striking how many respondents to our survey recounted being dismissed as ‘too complicated’ for support or treatment (or indeed their behaviour framed as too ‘challenging’). In the key findings, nearly half (42%) of respondents talked about not being listened to, taken seriously or understood when they were seeking help, nearly a third (30%) had problems with inaccessible services, over half (52%) had negative experiences, and over a quarter (26%) had been denied access to mental health services specifically because of their autism diagnosis.

The issues the report raises are due to a mixture of specific systemic problems and broader challenges with understanding and communication, but I would like to focus on the notion that we, autistic people, are an especially complex problem when it comes to supporting us.

A recurring problem for autistic people who seek help for mental health problems is being turned away based on the assumption that a certain level of anxiety, depression, distress in general, must be normal for us, and so isn’t something that can be helped. A practitioner might ask, “if it’s not possible to treat the autism, what can we even do?” Because the state of being autistic is commonly pathologised, it follows to many that it must be a state that is unpleasant and by necessity include suffering. However, autistic people who are happy, not depressed and not anxious exist. While it’s not surprising that being a neurological minority in a heavily neuronormative world might bring with it many challenges, it does not mean that we can’t be, and sometimes are successfully supported (including through appropriate counselling approaches) to be happier, more confident, less anxious and, at the most basic level, not suicidal.

What’s partly missing is a failure to approach the problems an individual is having as centred on how they’re impacted by society, and the interpersonal difficulties they may have faced, instead of centering the problem within the individual because they are autistic. It should never be about separating out the ‘autistic parts’ of a person’s experience (which I don’t think is possible anyway) and then only taking on the bits identified as ‘not autism’ for treatment. Instead, it should be about identifying what is causing distress collaboratively with the person, and addressing that with an acknowledgement of the broader context in which they exist. For all the challenges autism is associated with, it’s important to remember that, to many of us, there is also a huge amount of joy and sense of self tied in with our autistic ways of being.

Researchers and practitioners have only started to scratch the surface of the ways in which autistic people are impacted by trauma, for example, because often our reactions to traumatic experiences are written off as ‘part of the autism’, or traumatic events themselves dismissed as not actually traumatic by neurotypical standards. Just as we as a society have talked about other axes of privilege (gender, race, LGBTQ+), no person who fits reasonably well within the bounds of neurotypicality can fully intuit what it could mean for a person to grow up neurologically different, often surrounded by others who are not attuned to us or understand our ways of being in the world. However, a person can try to understand its implications, how to listen to and empathise with these experiences, and how much their own basic assumptions may fall short.

At the heart of this, and of a lot of our respondents’ experiences of not being believed, understood, listened to, is a breakdown in communication, the responsibility for which is too often placed with the autistic person, when it is more likely to be a mismatch in connection and expectation. Damian Milton calls this the ‘double empathy problem’, which has been demonstrated in a number of important studies (iv). Again, like the stories of our mental health struggles, the impact of this mismatch is known by the autistic community, but not yet well enough understood outside of it.

In a mental health context, this puts the onus on practitioners to listen carefully, give more time for communication, put aside assumptions, and importantly work alongside autistic people to figure out flexible solutions. As a population with so little understanding or effective pathways for support, yet such widespread mental health challenges, we are owed at the very least more time and flexibility.

Autism training should be led by autistic people with relevant experience and expertise; research and practice should be informed by the experience of being autistic in a neurotypical world. We are really not so complicated when presented through these perspectives. More importantly, with this understanding, I believe that more autistic people can be supported to be ok, happier, more confident, and less in crisis.

You can read the full AMASE mental health report and summary here: www.amase.org.uk/mhreport

REFERENCES

i www.autistica.org.uk/what-is-autism/signs-and-symptoms/ suicide-and-autism

ii https://amase.org.uk/resources/mhreport/

iii Milton, D., Mills, R., Jones, S. (2016). Ten Rules for Ensuring People with Learning Disabilities and Those Who Are On The Autism Spectrum Develop Challenging Behaviour.

iv http://dart.ed.ac.uk/insar-2019-virtual-symposium/